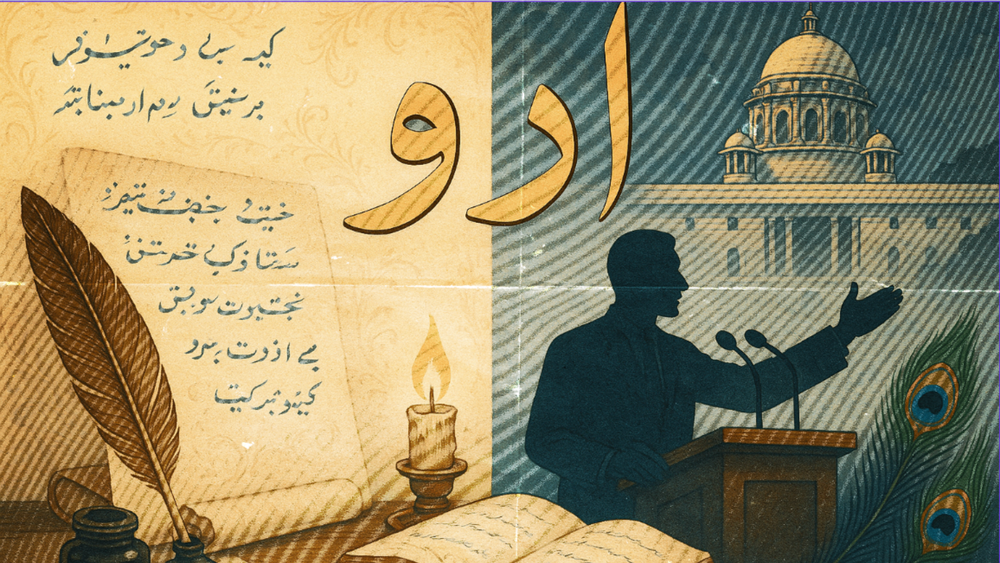

Urdu: The Language of Poets and Politicians

You see, Urdu carries the weight of three Ps;

Poetry- if you like your occasional tug in the heart-string.

Politics- if the newspaper and media noise occupies a special spot at the breakfast table.

And of course, Persian, one of its many parents that history won’t quite forget.

Somewhere amidst these realms, it carries the weight of religion too. In fact, Urdu occupies a spot in the many conflicts, celebrations and contradictions today. After all, India was where it took birth- how could it not?

The Urdu poet Khurshid Afar Bisrani writes about it quite bluntly:

Ab Urdu kya hai ek kothey kee tawaif hai

Mazaa har ek leta hai mohabbat kaun karta hai

In today’s scenario, Urdu has been used for applause, and abused for votes. Sure, Urdu will always find praise in Bollywood’s commercial needs and poetry sessions. Otherwise, it is today the “language of the Musalman;” a language spoken by 5.07 crore people as per the 2011 Census. Hindi and Urdu are so closely related that everyday spoken Hindi used by most Indians includes many Urdu words, making the two languages mutually intelligible for the majority.

And so, it remains a matter of contention. The Supreme Court stated in April 2025 that “Language is not religion. Language does not even represent religion. Language belongs to a community, to a region, to people; and not to a religion” after upholding the inclusion of Urdu alongside Marathi on a municipal signboard in Patur, Maharashtra.

However, it’s a little deeper than that. Urdu began to take shape more distinctly from the 12th century onward, after increased contact with Persian, Arabic, and Turkic languages due to successive Islamic invasions and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526) and later the Mughal Empire (1526–1858). The term "Urdu" itself is derived from the Turkish word ordu, meaning "camp" or "army", reflecting its origin as a lingua franca among soldiers in royal camps. A mixture of not just Turkish, Arabic and Persian but also Sanskrit, Hindi, Braj and Dakhani.

The year was 1837 when Urdu replaced Persian as the official language of the British East India Company in northern India. The language became a symbol of Muslim identity and played a significant role in the political movements leading to the creation of Pakistan. Therefore, while it is true that language has no religion, it was only the beginning of a controversy that would extend beyond the Constituent Assembly that once contemplated Hindustani, a blend of Hindi and Urdu, as the ideal national language.

Things took a steady yet explosive turn with this controversy. In August 1967, communal riots broke out in Ranchi and Hatia (then in Bihar), triggered by tensions over the Urdu language and Ram Navami festival. This resulted in 184 deaths. In 1994, what began as a protest outside Karnataka’s Doordarshan office for the broadcast of an Urdu news bulletin ended in 25 deaths and property worth Rs 1 Crore damaged.

Today conflicts around India’s languages have only gotten more vibrant, often finding a cosy nook in political debates and budget allocations. The Urdu controversy reawakened to life after Rs 100 crore was allocated for Urdu schools in the Karnataka government’s 2025 budget, Rs 100 crore was allocated for Urdu schools. It was the ₹32 crore reportedly allocated for the state’s very own language Kannada, that fueled the fire on X (Twitter). Oof, that’s just touchy.

However, this is where it gets interesting: the funds for the National Council for the Promotion of Urdu Language had nearly doubled in just five years. From ₹45 crore in 2013-14, it had risen to ₹84 crore in 2019-20- a solid 45% rise.

Let’s take a pause now; who is this for again? Clearly not the Urdu speakers since reality goes far beyond the screens of political mileage or appeasement politics.

In 2019, an independent report, “A New Agenda For The Education Of Indian Muslims in the 21st Century”, noted a corresponding decline in Urdu particularly sharp among school-going Muslim children. Only about 0.8% of all Indian students are enrolled in full Urdu medium schools nationwide.

Why? Because the language no longer ensures employment in the government or private sectors. And it surely is no cakewalk with just fewer Urdu-medium schools, limited availability of quality Urdu textbooks, and a shortage of qualified Urdu teachers in India today.

It so appears that it is celebrated on stage yet sidelined in schools, embraced in verses but excluded from vocational promise. And so Urdu once the language of poets, is also the language of politicians; A convenient symbol that can project inclusivity or stir resentment anytime.

Now, where does one truly draw the line between preservation and performance? We’d just have to ask the poets/politicians to answer this themselves.